World War Two

There could be no more appropriate beginning to this section than the video clip of ex-prisoner-of-war Arthur Leggett of Perth reciting two poems about mateship, the one factor that kept many young men alive in horrific circumstances. Unfortunately, the clip was extracted from an amateur concert, so is not as good as we would like.

Arthur spent 6 years of his young life as a POW in German hands and was part of the march across east Germany, in one of the worst winters of those years. This amazing man was born in 1918, and was in his 90s when he recited these poems. He has written a fascinating autobiography – “Don’t Cry For Me”- which we highly recommend.

Australians will appreciate his accomplishments (since his 70s), which include marathons, the Avon Descent (a tough white-water challenge), a motor-cycle solo ride across the Nullabor and walking the full length of the Bibbulman Track. He still gives amusing public talks, mentors at a high school and is in demand for ANZAC Day and other ceremonies.

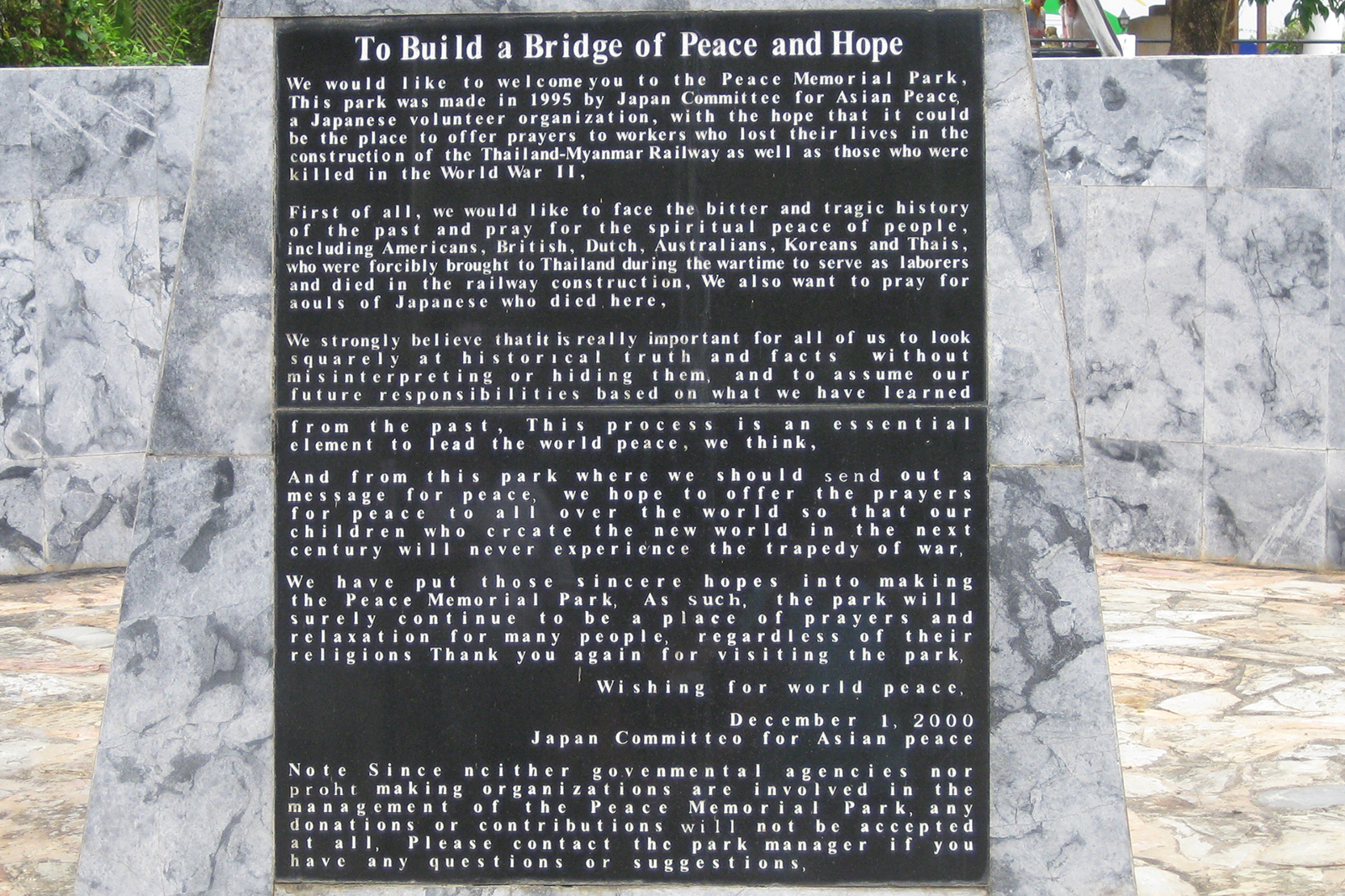

The Burma-Thailand Railway

Numerous books have been written by survivors of this dreadful experience, including The War Diary of Weary Dunlop, a well-known, but fanciful movie made (The Bridge on the River Kwai), and a recent one (The Railway Man) released. The prisoners-of-war who wrote these books had experienced the horrors of the Death Railway, so reading their accounts is the best way to gain an understanding of what happened… we will not even try to describe it.

The Quiet Lion Tour

Every April, for some years now, the Burma-Thai Railway Memorial Association (BTRMA) in Perth, Western Australia, has organised a fascinating tour to Thailand to visit Hell Fire Pass, other significant features of the Death Railway, Kanchanaburi, the cemeteries, and museums.

Veterans, who suffered so much during the building of the railway, accompany the group and describe what happened there. Anzac Day begins with a very moving Dawn Service in Hellfire Pass, and later in the morning a more official ceremony takes place in Kanchanaburi.

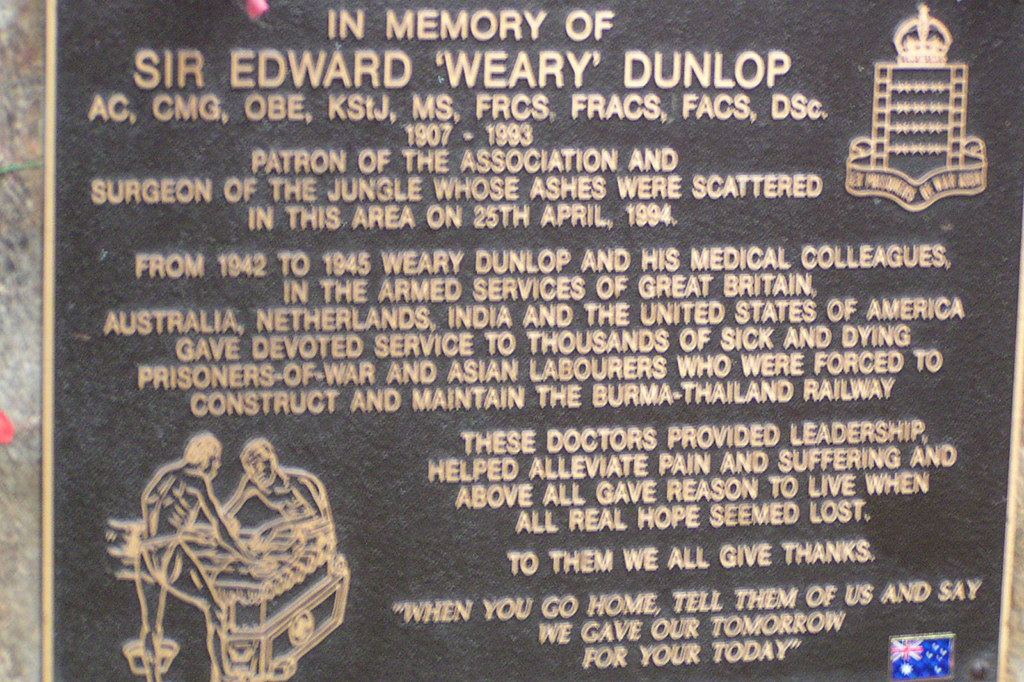

We first went to Hellfire Pass in 1995, before it was cleared and developed into its present form. We have joined the Quiet Lion Tour several times. The name is a reference to Dr “Weary” Dunlop from Victoria, who is so devotedly remembered for his skills, compassion and bravery in caring for and defending the often mortally ill men who were expected to work, no matter what, and were brutally treated by the Japanese and Korean soldiers.

The inscription on the plaque reads:

In memory of Sir Edward “Weary” Dunlop

AC, CMG, OBE, KStJ, MS, FRCS, FRACS, FACS, D Sc.

1907-1993Patron of the Association and surgeon of the jungle, whose ashes were scattered in this area on 25th April 1994.

From 1942 to 1945 Weary Dunlop and his medical colleagues in the Armed Services of Great Britain, Australia, Netherlands, India and the United States of America, gave devoted service to thousands of sick and dying prisoners-of-war and Asian labourers who were forced to construct and maintain the Burma-Thailand Railway.

These doctors provided leadership, helped alleviate pain and suffering, and above all gave reason to live when all real hope seemed lost. To them we give thanks.

“When you go home, tell them of us and say we gave our tomorrow for your today.”

In the clip below ex Prisoner of War, the late Bill Haskell from Perth, Western Australia tells the tour group about the horrific day-to-day experiences of the prisoners-of-war at Hintok Camp and of the PoWs who worked on this section of the Burma-Thailand Railway during WW2.

A valuable feature of the tour is the inclusion of more than 30 young people, around 15 years old, from schools around the State. They are all visibly affected by what they see and learn here. They also have a wonderful sightseeing opportunity.

Skeletons

Here is a story written in May 2007 by one of these participants. Her name is Josie Woodman and she was just 15 when she wrote it as part of a school requirement after the tour. She is now a doctor in Melbourne and is Trish’s grand-daughter.

A misty sunlight filtered through my closed eyelids. The hum of a thousand insects sang a shrill welcome to the morning. The drip of water from the surrounding rainforest mixed with the rattle of bamboo, as a light breeze ran past, leaving the air still. The warmth made me relax, and I lazily opened my eyes. The misty light danced in front of them, as I tried to focus.

Eventually I saw a stained piece of netting, suspended above me. It played around in another warm breeze, jumping and turning like a rough sea. I stared at the netting as I slowly comprehended the situation. The yellow netting and the sounds of the early morning rainforest could mean only one thing. I wasn’t dead yet.

I slowly turned my head to the side, and took in the sight before my eyes. A long tent made of the same dirty netting extended before me. Closely spaced beds, little more than rough bamboo frames with more netting stretched over them, ran along the side of the room.The hazy sunlight reflected off the walls, blocking my view of what was outside.

I gazed againat the row of beds and noticed a strange thing. They all had a frail skeleton lying on them, some strapped down, others looking as if they were just thrown there. My eyes watered at the glare of the sun, so I had to be content at just observing the bed next to me.

This skeleton had stained yellow bones, and one bone of a leg dangling off the edge of the bed. A thin tube came from his arm, and as I traced it upwards, found it led to a smashed bottle, half filled with a clear fluid. It looked like a hospital drip, but who would bother trying to nurse a skeleton? As I asked myself this question, I noticed something else about the figure next to me. Its chest was rising and falling. Softly, yet surely. It must be alive

I oticed the thin skin tight over his bones. It fell away sharply from his chest, creating a wide cavern that should have been his stomach. His yellow skull had a light scattering of hair on it.

As I was still trying to comprehend that this bag of bones could possibly be alive, I had a sudden urge to look up to the side of my own bed. It was like I knew what was going to be there, but had to try to suspend the confirmation of my fear. My heart fell as my sight fell on a broken bottle. The liquid in it was less than half full. I traced its path, through a thin piece of tubing, and onto my chest. I looked down to see a needle sticking into the bone that lay across my chest

I gazed at it for a while, looking at the thin fingers at the end of it. I moved one of my fingers, and the bone twitched. I tried to raise my hand, and the bones shuddered, not strong enough to lift themselves up. I looked at my chest, and was surprised to see that it was the same as the poor man next to me.

I cold see the outline of each bone. The dark shadow that fell away on the other side of each rib pulled the skin tight. My stretched skin was wrapped around each bone, so thin that I could almost see through it. I was no more than a skeleton myself.

I looked back up to my drip, to see that it was almost empty. I looked at it with surprising calmness. Like trying to remember a dream, it was hard to realise why I was so calm. I tried to gather my thoughts. I was sick. I knew that for certain. The drip in my arm and the hospital around me meant that someone must be caring and treating me. Hopefully they would come before all the liquid ran out of the bottle.

I heard some light footsteps, then silence. I waited, straining my ears for sounds of life. Dull footsteps trudged nearby, slow and peaceful. The sunlight, not so misty now, fell in a sharp beam across my face. I squinted my eyes, but didn’t have the strength to shade my eyes with my hand. I felt like someone was pressing me down. I felt like I was being crushed under the drowsy light.

I can’t remember how long I was asleep for, but it must have been a while. The sharp sunlight was gone, yet the tent was bright. The drone of the insects was replaced by the noise of the camp around me. More footsteps, heeavier this time, like lead boots, marched past.

The smell of the place hit me. I don’t know why I hadn’t smelt it before. The clean, fresh yet medical smell of a hospital was replaced by the stink of uncleaned wounds and burnt rice. A thousand other disgusting odours passed by my nose, but I tried desperately not to smell them.

Gunshots in the distance sounded out, echoing sharply into the tent. The camp continued, people talking, working. A severe volley of gunfire must be a regular occurrence.

I glanced at my drip and was glad to see it was nearly full. I looked over to see if my neighbour’s drip had been refilled, but he was not there. An empty bed, with the empty drip hanging loose, stared back at me.

I don’t know how long I stared, but I know I didn’t blink once. The skeleton must have died. One of the groups of footsteps passing outside the tent stopped. I could see the top of a rip in the netting open, and then fall back into place again as the group shuffled in.

My heart raced as they walked up to my bed. There were four men. Two of them were supporting their companion, who was collapsed limp between them. The fourth, an old man, was directing the rest over to my neighbour’s bed. I watched as they lay the limp man down.

The old man grabbed the empty drip and bottle and walked away. I stared at the face of my new neighbour, and gave a start as he tipped his head to face me. The whites of his eyes had turned blood red, and were rolling madly around in their sockets.A white liquid spurted out of his mouth as he coughed, gasping for air. The old man returned and blocked my view for a moment as he hung the drip up and inserted the needle into the sick man.

I tuned out as the old man started conversing with the two healthy men. They started strapping my companion to his bed, I felt another wave of tiredness sweeping over me, crushing me down to sleep; yet I struggled to stay awake. I heard the old man talking about the hospital.

“This one here,”he said, before interrupting himself with a hollow knock at the end of my bed, “and about two others, should be up for parade tomorrow. We really should keep them a bit longer, but there are others who are worse, and we need the beds.”

Parade. The word stuck in my mind, as the memory came back to me. Parades!. There were hundreds of men lined up in rows. Some had wooden legs, some had gaping holes as tropical ulcers ate their fles,h and some were like me, as thin as a skeleton.

Japanese guards marched up and down the rows, yelling and sometimes giving gruesome and violent demonstrations of their power. I wanted to be better and maybe work up some flesh to my bones, maybe become human again. But was it worth it?

Parades, hard work and pain were more than I could bear to think about. It was hard to tell which the better option was. Dying a cholera patient in a primative jungle hospital doesn’t seem like a good option. Conuting off my disappearing companions, not knowing which moment would be my last, whether or not I would just fall asleep and never wake up. Or I could die working, tortured with strenuous labour and brutal punishments, repressed, humiliated and crushed under such oppression it would not be worth fighting against. I wondered if I had a choice at all, whether I would just will myself to die in my sleep, or if I would get better and join my mates again, just to be tortured and killed. Just one more casualty on the hellish Thai-Burma Railway.

The Prisoners-of-War

The horrors of working on the Railway

Illness was inevitable due to the starvation diet, the bashings, the long working hours –no matter how ill, the lack of footwear or clothing, the enervating, severe weather conditions. Malaria, dysentery, beri beri (from lack of vitamins), and cholera were rife, but there were no medicines. Cuts and wounds on the legs and feet soon turned into tropical ulcers, often leading to amputation.

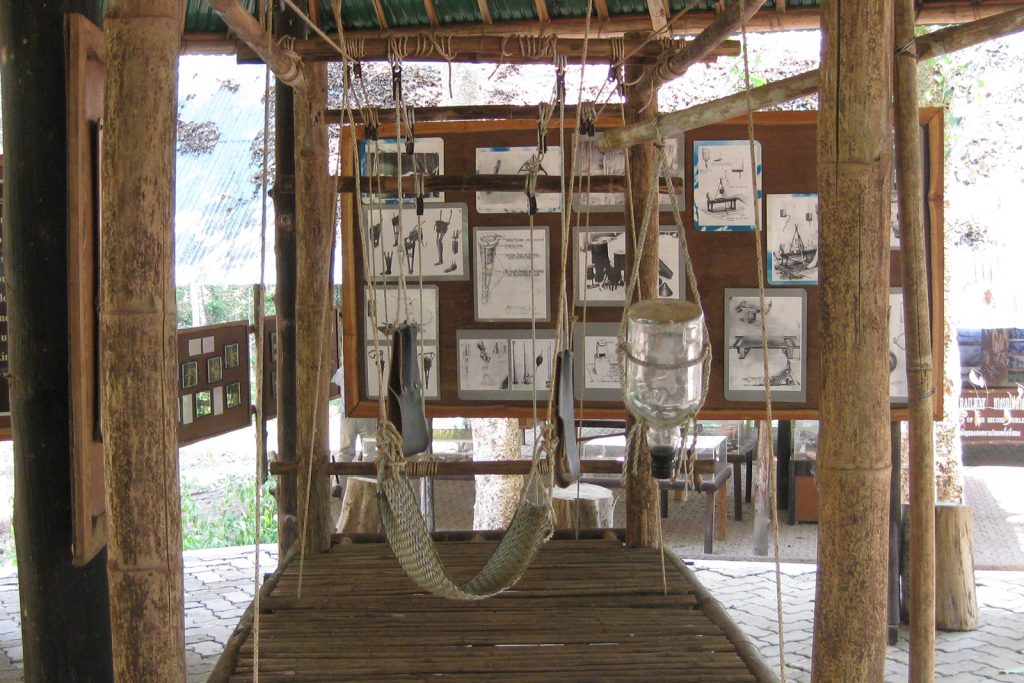

The surgeons, doctors, other medical men and orderlies, did a heroic job trying to keep the young men alive or at least ease their suffering. They became amazingly innovative in turning bamboo, used tins, etc into medical equipment.

There were over 1,000 leg amputations as a result of tropical ulcers, but the chance of surviving was less than 20%.

Here Bill Haskell eloquently describes the suffering of cholera victims and the brilliant and resourceful way the doctors, especially their hero “Weary” Dunlop, devised a method of replacing fluid in the victims. He also tells us about other dreadful health problems and how the medical staff dealt with them. Video clip of Bill Haskell No2

Their ordeal did not end with the completion of the railway. Many were shipped to Japan to work in the coal mines, but –tragically – hundreds lost their life when Japanese ships were sunk by torpedo, aircraft or submarine, with few survivors. Some are buried in Kranji Cemetery, Singapore.

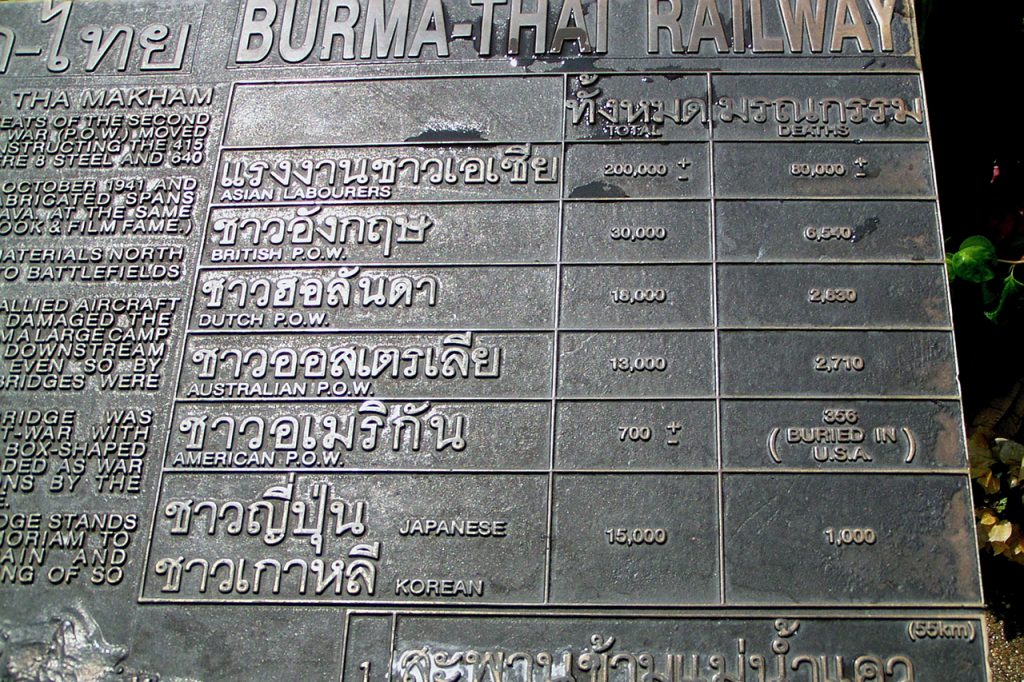

Asian labourers (approximate): Total 200,000; Deaths 80,000

British POW: Total 30,000; Deathes 6,540

Dutch POW: Total 18,000; Deaths 2,830

Australian POW: Total 13,000; Deaths 2,710

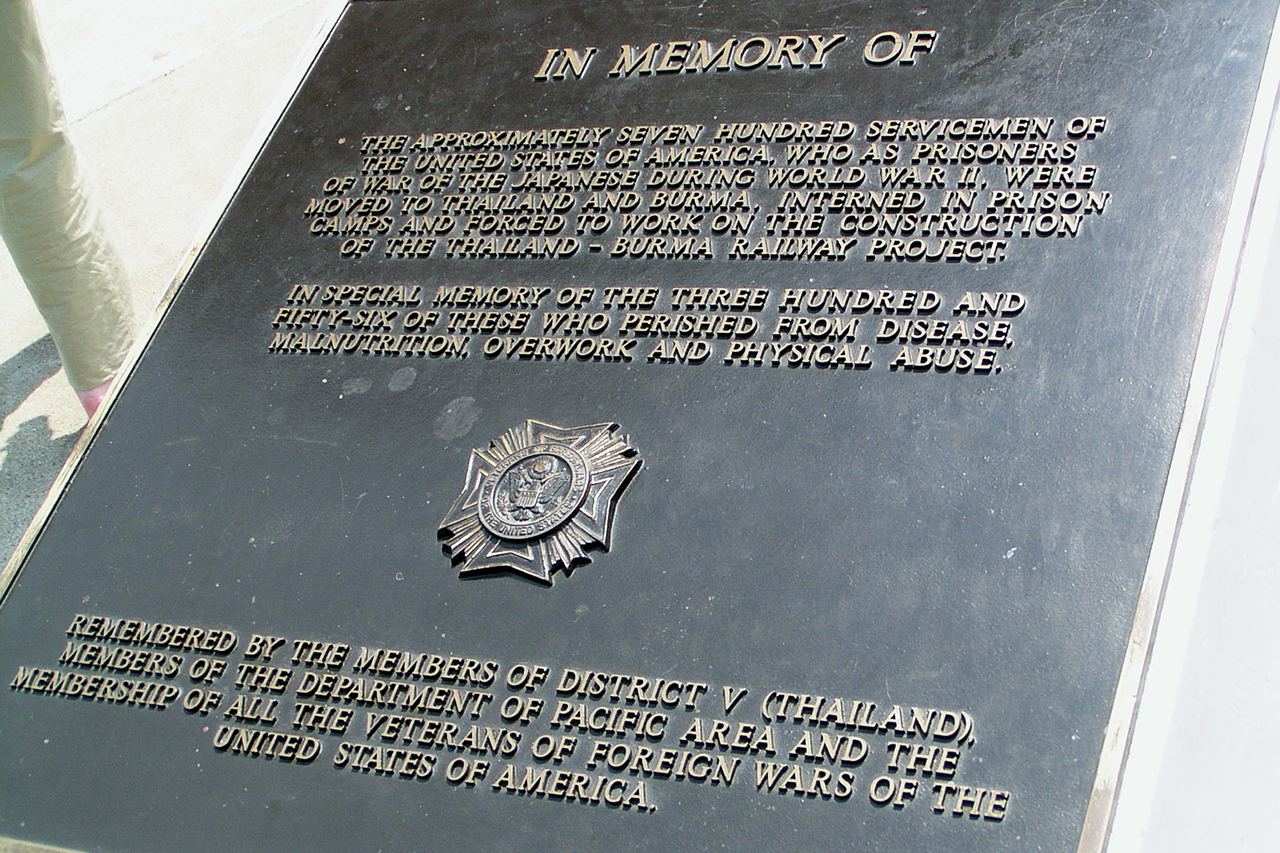

American POW (approximate): Total 700; Deaths 356 (buried in USA)

Japanese and Korean: Total 15,000; Deaths 1,000

During the Quiet Lion Tours to Thailand, Bill Haskell eloquently describes the suffering of cholera victims and the brilliant and resourceful way the doctors, especially their hero “Weary” Dunlop, devised a method of replacing fluid in the victims.

Plaque inscription: In memory of the approximately seven hundred serviceman of the United States of America, who as prisoners-on-war of the Japanese during World War Two, were moved to Thailand and Burma, interned in prison camps and forced to work on the construction of the Thailand-Burma Railway.

In special memory of the three hundred and fifty six of those who perished from disease, malnutrition, overwork and physical abuse.

Remembered by the members of District V(Thailand), members of the Department of Pacific Area and the membership of all the veterans of foreign wars of the United States of America.

Death

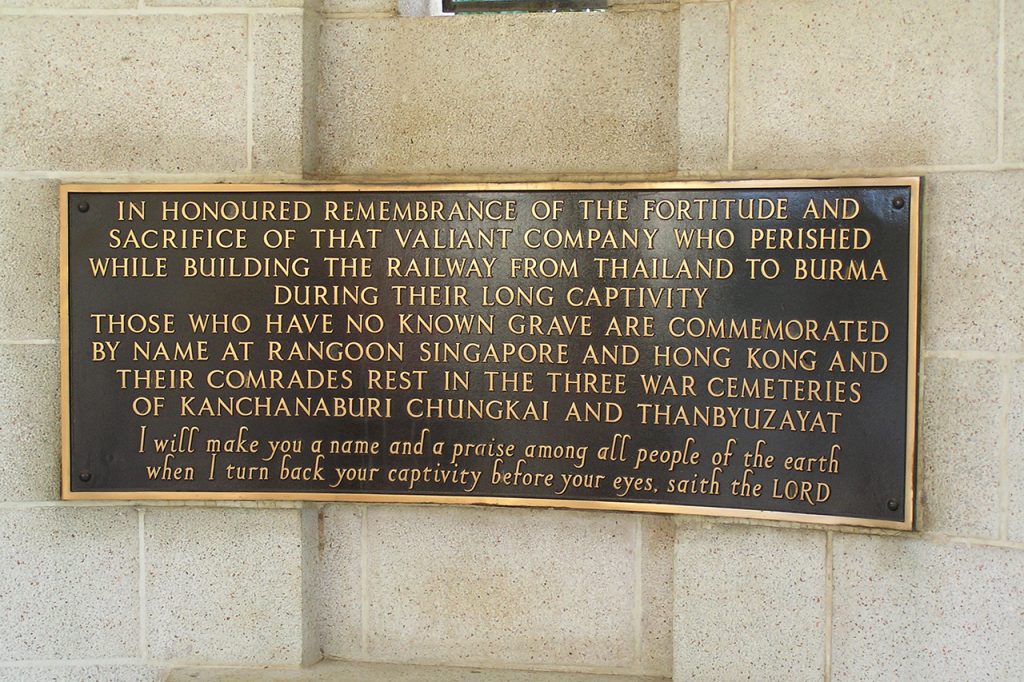

Those who died are remembered in Thailand with honour, and their graves are tended in beautiful settings.

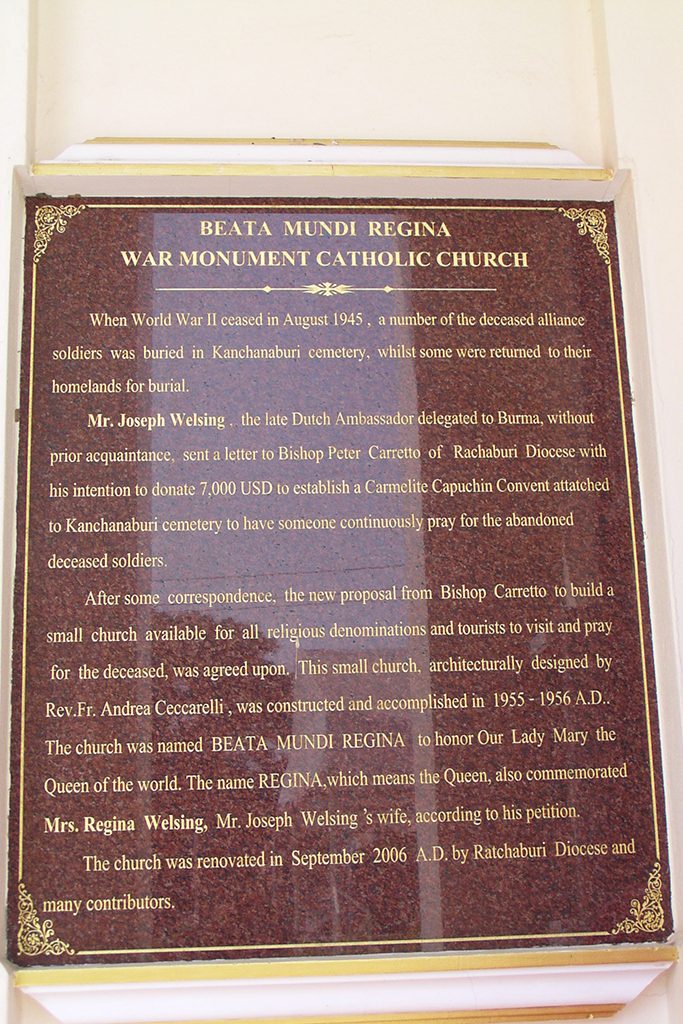

Church

This small church, built in 1955-56, is near the Kanchanaburi Cemetery. It is named Beata Mundi Regina, (Our Lady, Queen of the World) and is a quiet place for tourists and others to pray for the unknown dead soldiers.

The Wampo Viaduct

Video showing the Wampo Viaduct, a section of the Burma-Thailand Railway, built by the prisoners of the Japanese. It shows how difficult this must have been to construct.

The Three Pagoda Pass

Short clip shows the memorials on the border between Thailand and Burma.

The Dawn Service in Hellfire Pass, 2011

Excerpts of the always poignant Anzac Day Dawn Service in “Hellfire Pass”, Thailand. The entrance of the Catafalque Party, the lone piper, dawn coming up. We hear the then Governor-General of Australia – Dame Quentin Bryce – as she speaks to each of the ex-Prisoners-of–War who are present.